The shipping containers were a familiar sight to the villagers of northern Mozambique’s remote and troubled Afungi peninsula: a dozen steel boxes lined up end-to-end with a guarded gate in the middle. They formed a makeshift barricade at the entrance to an enormous natural gas plant that the French energy giant TotalEnergies was building in a region plagued by a violent Islamist insurgency.

The villagers had been caught in the crossfire between the Mozambican army and ISIS-affiliated militants. Having fled their homes, they had gone to seek the protection of government soldiers. Instead, they found horror.

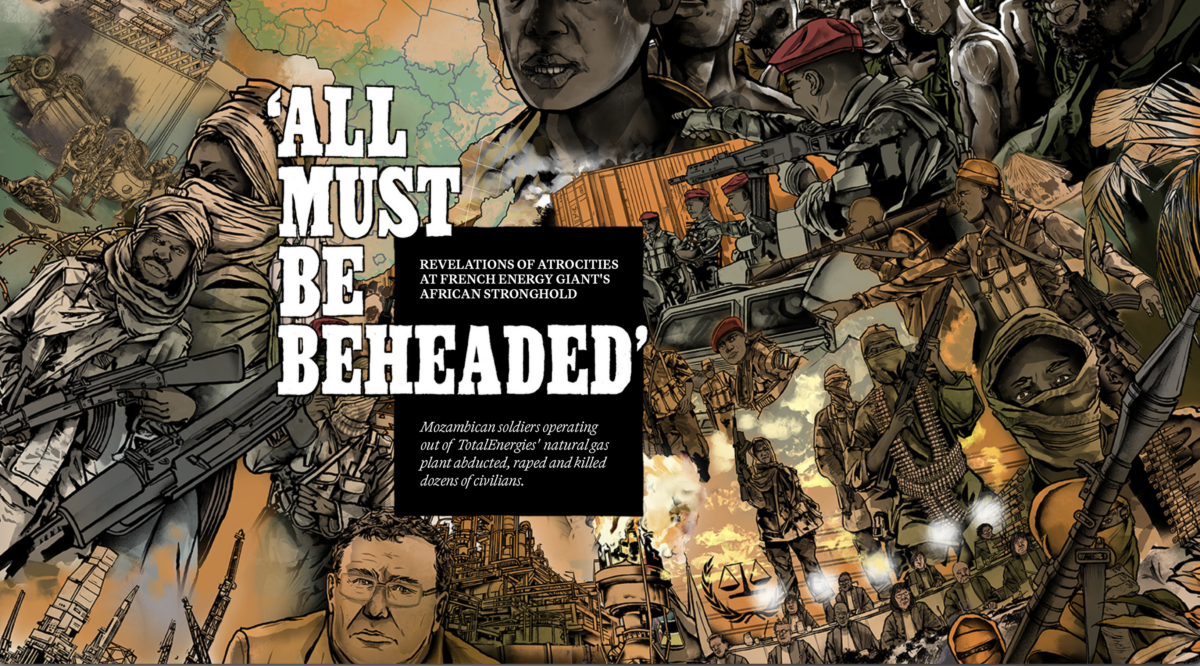

Meanwhile, the soldiers accused all the men — a group of 180-250 aged from 18 to 60 — of belonging to al-Shabab. The soldiers stripped them of identity documents, phones and money, whipped them with thorn branches and threatened to kill them. “We don’t want any boy or man [left alive],” Mwamba heard a soldier say. “No matter how old he is. All must be beheaded.”

Then they crammed their prisoners into the shipping containers on either side of the entrance, hitting, kicking and striking them with rifle butts.

The soldiers held the men in the containers for three months. They beat, suffocated, starved, tortured and finally killed their detainees. Ultimately, only 26 prisoners survived.

Through interviews with survivors and witnesses, and a door-to-door survey of the victims’ villages, I was able to reconstruct a detailed account of the atrocities carried out during the summer of 2021 by a commando unit led by an officer who said his mission was to protect “the project of Total.”

News of the massacre can only add to the gathering sense of catastrophe that now surrounds a project that was once — together with the development of a second gas field by ExxonMobil — heralded as the biggest private investment ever made in Africa, with a total cost of $50 billion.

The women were released after a day or two. But for the next three months, the soldiers kept the men locked in the windowless metal containers in 30-degree Celsius (85 degrees Fahrenheit) heat. So packed in were they, said Amadi, 23, a father of one, that “we couldn’t even sit. We had to stand up, like dried fish.”

There were no toilets, forcing the men to soil themselves. The soldiers starved their prisoners of food and water for days on end. When they relented, supplies were limited to a fistful of rice and a sip of water from a bottle cap.

With their other prisoners, the commandos settled into a routine of abuse. They would work in shifts, arriving from inside TotalEnergies’ compound in the morning, or from bunks set up in a neighboring container, to resume a steady schedule of beatings and torture. “That became our normal life,” Bihari said.

As time passed, the soldiers became more inventive. They held knives to their prisoners’ throats and threatened to behead them. They brought them out of the containers to lie on the ground on their backs, looking up at the sun for hours. They made them strip and kiss each other.

One man who tried to run “was shot and beheaded,” Bihari said. The same fate awaited anyone else who tried to escape, the soldiers warned. “It’s better that you are killed here,” they said.

And killing them they now were. One day, the doors opened to reveal a plainclothes officer whom Salimo recognized as a man who had taken down names and addresses at Patacua. “He told us he wanted some guys to go with him to help him to dig a hole where they could push trash,” Salimo said. “You couldn’t say no. Fifteen people were taken away to dig the trash.” Those 15 were never seen again.

Three days later, the same thing, with another group. This time, Salimo said, “it was very clear that they were being taken to be killed.” The soldiers placed empty rice sacks over the men’s heads. They beat and stabbed them as they led them away.

In time, these trips to the trash pile became regular, too. “They were just taking people randomly,” said Figo, 26, a trader. “Like, ‘You, you and you.’” The soldiers had a code for when a new round of executions was due: It’s time to chop wood. “It means: Kill them,” Maria said.

Inside the containers, Moussa said, “our number was going down. One day, this container. Two days after, the other. They didn’t say why. They just kept doing it until we were almost finished.” By September 2021, of the original 180-250 prisoners, Moussa said, “only 26 of us were left.”

The survivors were finally released that month when they were discovered by the Rwandan army, which had been deployed to fight al-Shabab under a three-way deal between Mozambique, Rwanda and France.

Since becoming CEO and chairman of France’s biggest company in 2014, Patrick Pouyanné has grappled with the dilemma facing all 21st-century oil and gas bosses: How to square the world’s appetite for fossil fuels with its simultaneous demand for their elimination.

His answer, outlined in speeches and public appearances over the years, has been a strategy of two parts: to prioritize natural gas, which emits half the carbon of coal when burned, as a “transition” fuel; and to operate whenever possible outside the restrictive legal environments of North America and Europe.

The 2010 Deepwater Horizon blowout — which killed 11 crewmen and whose oil slick devastated hundreds of miles of Gulf of Mexico coastline — was a pivotal moment for the fossil fuel business, Pouyanné told an audience in London in 2017.

The “absolutely enormous” penalties of $62 billion to $142 billion (depending on the calculation used) imposed on the British energy giant BP heralded the arrival of what Pouyanné called a new, prohibitive “legal risk” of operating in places where fines of that magnitude might be imposed.

Pouyanné’s solution was to seek out less-regulated territories in the Middle East, where the energy company’s origins lay, and Africa, the birthplace of Elf Aquitaine, the oil producer absorbed by Total in 1999.

In recent years, there have been many examples of energy companies being prosecuted for atrocities in precisely the kind of faraway lands favored by Pouyanné.

In 2022, after decades of delay, ExxonMobil was ordered to stand trial in the United States in a case brought by 11 Indonesian villagers for murder, rape and torture carried out by soldiers whom Exxon paid to guard a gas field in Aceh; Exxon settled the case in 2023. Also in 2022, Lafarge, a French cement maker, was fined $778 million by the U.S. Department of Justice for paying $6 million in bribes and protection money to ISIS in Syria.

Last September, the former chairman and chief executive of the former Lundin Oil, which has since changed names several times, went on trial in Stockholm. The company has been accused of complicity in atrocities perpetrated from 1999-2003 by Sudanese soldiers whom they asked to secure a drill site in what is now South Sudan.

This June, a Florida court ordered the U.S. banana giant Chiquita to pay $38 million to the families of eight Colombian men killed between 1997 and 2004 by a paramilitary death squad securing its facility.

The parallels to what happened in Afungi are clear. The commandos were based on TotalEnergies’ compound. They ran their detention-and-execution operation from the petroleum giant’s gatehouse. And while the Mozambican Ministry of Defense refuses to comment on the massacre or say whether the commandos were part of TotalEnergies’ Joint Task Force, an unnamed brigadier who commanded them told Mozambican state TV on July 3, 2021, that his mission was to defend Total.

In addition to sparking interest among prosecutors in France or elsewhere, the massacre will also likely stir unease among banks and state lenders from Britain, France, Italy, Japan, Netherlands, South Africa and the U.S. who have agreed to back TotalEnergies’ Mozambican project with $14.9 billion in loans but have yet to hand over the money.

For their parts, TotalEnergies and Mozambique seem determined to allow no further disruption to the project on which Pouyanné’s grand strategy for 21st-century oil and gas rests, but which has so far cost his company billions and made it nothing in return. Anticipating a restart in the next few months, neither has recognized the atrocities at Palma or Afungi.