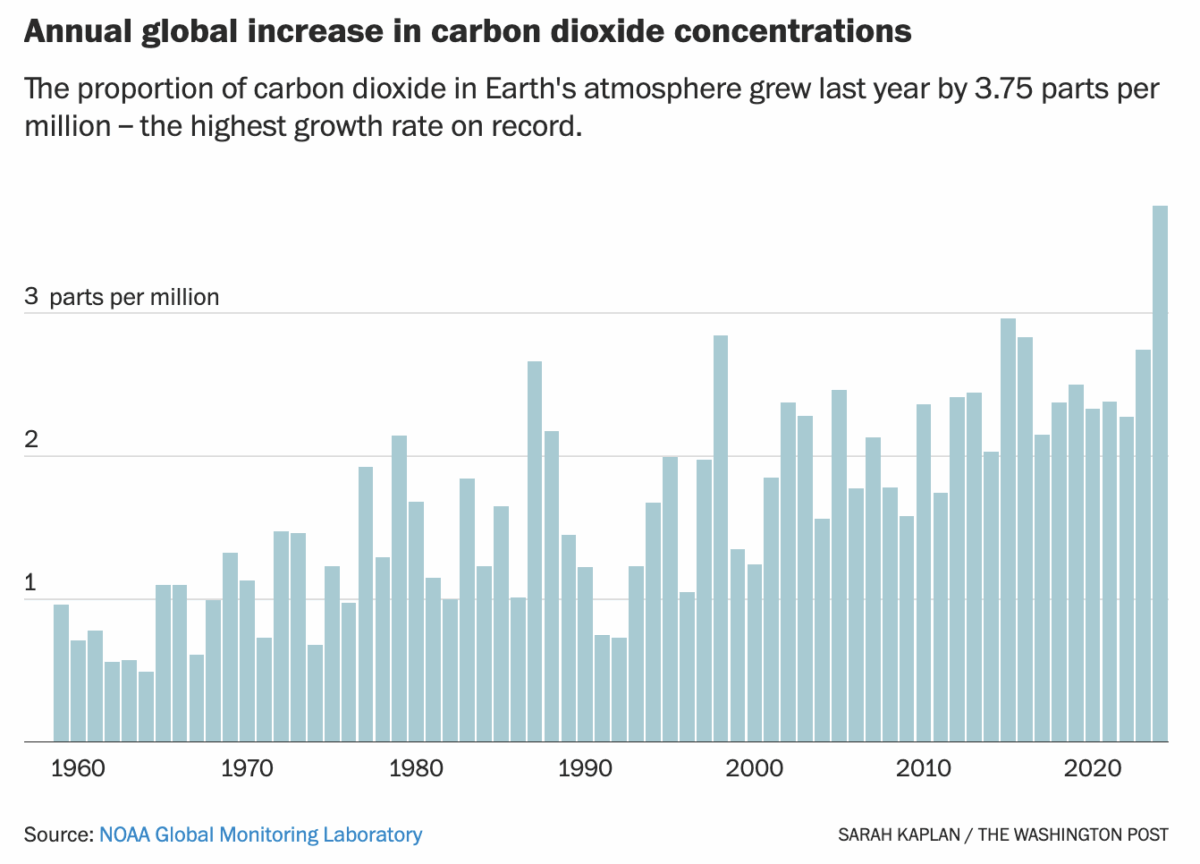

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Global Monitoring Laboratory on Monday released data showing the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere increased by 3.75 parts per million in 2024. That jump is 27% larger than the previous record increase, in 2015, and puts atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations at a level not seen in at least 3 million years.

“This is next-level high,” said Glen Peters, who studies the carbon cycle at the CICERO Center for International Climate Research in Norway. “So it raises that concern of ‘why is it much higher than expected?’”

Though the vast majority of planet-warming gases come from people burning fossil fuels, a separate study released Tuesday suggests that last year’s sudden spike was likely driven by a different force: the deterioration of rainforests and other land ecosystems amid soaring global temperatures.

The land and oceans have historically taken up about half of the greenhouse gases people emit. Without these places that absorb CO₂ — known as carbon sinks — global temperature rise would be twice the roughly 1.3˚C (2.3˚F) the world has already endured.

The preliminary analysis published Tuesday shows how extreme drought and raging wildfires unleashed huge amounts of carbon from forests last year, effectively canceling out any pollution they might have absorbed.

Using multiple global vegetation models as well as data from NASA’s Orbiting Carbon Observatory, which measures carbon dioxide from space, the researchers estimated that the land took up about 2.24 fewer gigatonnes of carbon over the 12-month period.

Depending on how it’s calculated, the change either zeroed out the land sink or turned terrestrial ecosystems into a net source of carbon pollution.

Ciais and Peters worked with a team of international researchers to analyze sources and sinks for carbon over the course of the past El Niño event, which spanned roughly from July 2023 to June 2024.

“This tropical dryness is basically shutting down CO₂ uptake,” Ciais said.

The analysis only extends through June [January 1st to July 1st 2024], when the El Niño was declared over. But the scientist said he was even more concerned by what came next.

Though the end of the climate pattern typically signals the return of moisture, in the second half of last year the extreme drought in the Amazon surged to encompass nearly 40% of the rainforest. Across South America, many rivers fell to record-low levels. Wildfires ripped through the parched landscape, burning an area larger than California.

On the other side of the Atlantic, an equally severe drought had descended on the rainforests of central Africa. By midsummer, more than half of the region was experiencing “extreme” conditions, according to the ECMWF data. Satellite measurements showed that the forests were absorbing far less of the sun’s radiation than normal — an indication of trees dying or becoming too stressed to perform photosynthesis.

“It’s a bad cocktail of an El Niño followed by a very strong dry event, so the plants don’t get a break,” Ciais said. “This has no equivalent during previous Niño events.”

It is still unclear why the world’s forests suffered so intensely last year. It may be a simple case of bad luck — a severe El Niño event that happened to coincide with a randomly occurring drought. Or it could be a sign of an emerging climate feedback loop, in which rising temperatures trigger the release of more carbon, which then causes the planet to heat up further.