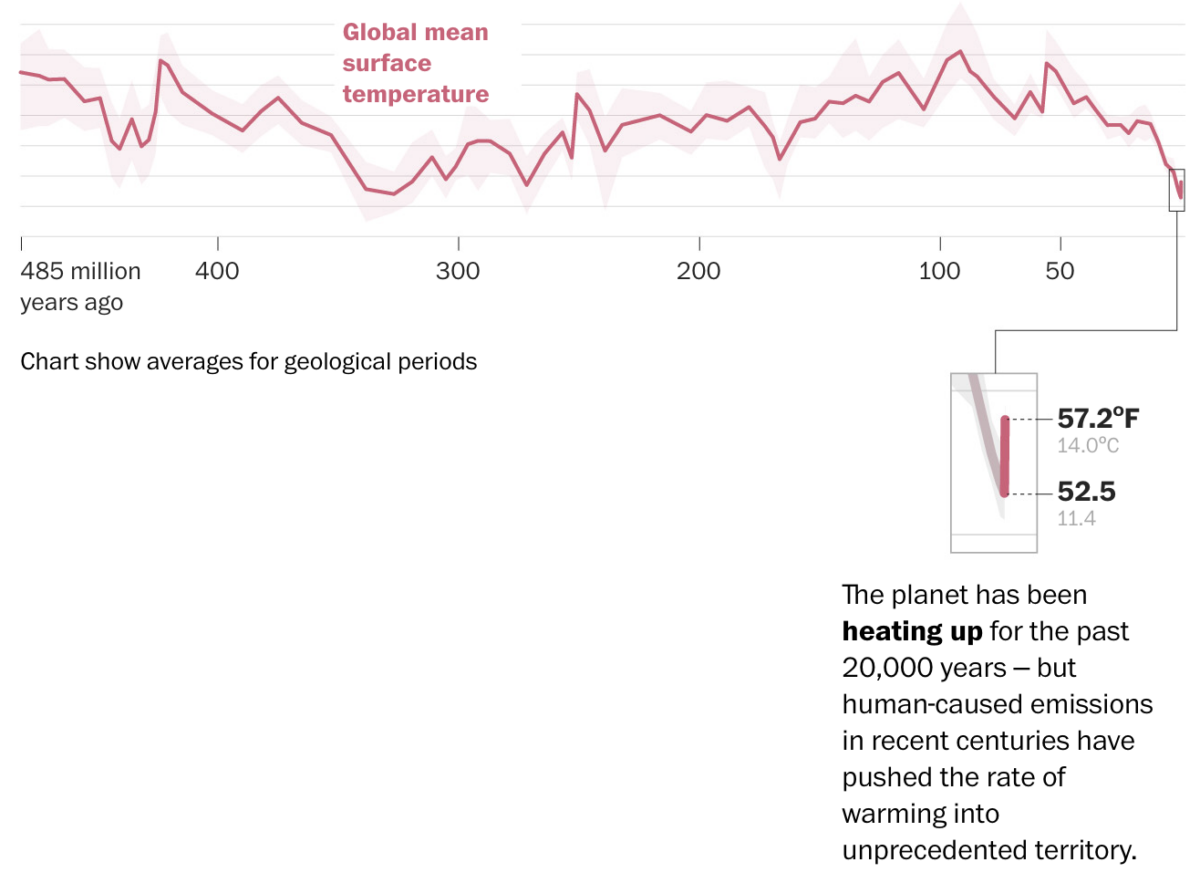

The timeline, published Thursday in the journal Science, is the most rigorous reconstruction of Earth’s past temperatures ever produced, the authors say. It shows the intimate link between carbon dioxide and global temperatures and reveals that the world was in a much warmer state for most of the history of complex animal life.

At its hottest, the study suggests, the Earth’s average temperature reached 96.8˚F (36˚C) — far higher than the historic 58.96˚F (14.98˚C) the planet hit last year.

The revelations about Earth’s scorching past are further reason for concern about modern climate change, said Emily Judd, lead author of the study. The timeline illustrates how swift and dramatic temperature shifts were associated with many of the world’s worst moments — including a mass extinction that wiped out roughly 90% of all species and the asteroid strike that killed the dinosaurs.

At no point in the nearly half-billion years that Judd and her colleagues analyzed did the Earth change as fast as it is changing now, she added:

“In the same way as a massive asteroid hitting the Earth, what we’re doing now is unprecedented.”

But, in keeping with decades of past research on climate, the chart hews closely to estimates of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, with temperatures rising in proportion to concentrations of the heat-trapping gas.

“Carbon dioxide is really that master dial,” Tierney said. “That’s an important message … in terms of understanding why emissions from fossil fuels are a problem today.”

At the timeline’s start, some 485 million years ago, Earth was in what is known as a hothouse climate, with no polar ice caps and average temperatures above 86˚F (30˚C). The oceans teemed with mollusks and arthropods, and the very first plants were just beginning to get a toehold on the land.

Temperatures began to slowly decline over the next 30 million years, as atmospheric carbon dioxide was pulled from the air, before plummeting into what scientists call a coldhouse state around 444 million years ago. Ice sheets spread across the poles and global temperatures dropped more than 18˚F (10˚C). This rapid cooling is thought to have triggered the first of Earth’s “big five” mass extinctions — some 85% of marine species disappeared as sea levels fell and the chemistry of the oceans changed.

An even more dramatic shift occurred at the end of the Permian period, about 251 million years ago. Massive volcanic eruptions unleashed billions of tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, causing the planet’s temperature to shoot up by about 18˚F (10˚C) in roughly 50,000 years. Acid rain fell across the continents; marine ecosystems collapsed as the oceans became boiling hot and depleted of oxygen.

“We know it to be the worst extinction in the Phanerozoic,” Tierney said. “By analogy, we should be worried about human warming because it’s so fast. We’re changing Earth’s temperature at a rate that exceeds anything we know about.”

The study also makes clear that the conditions humans are accustomed to are quite different from those that have dominated our planet’s history. For most of the Phanerozoic, the research suggests, average temperatures have exceeded 71.6˚F (22˚C), with little or no ice at the poles. Coldhouse climates — including our current one — prevailed just 13% of the time.

This is one of the more sobering revelations of the research, Judd said. Life on Earth has endured climates far hotter than the one people are now creating through planet-warming emissions. But humans evolved during the coldest epoch of the Phanerozoic, when global average temperatures were as low as 51.8˚F (11˚C).

Without rapid action to curb greenhouse gas emissions, scientists say, global temperatures could reach nearly 62.6˚F (17˚C) by the end of the century — a level not seen in the timeline since the Miocene epoch, more than 5 million years ago.

And for the billions of people who are now living through the hottest years ever recorded — and facing a hotter future still — Judd said the timeline should serve as a wake-up call. Even under the worst-case scenarios, human-caused warming will not push the Earth beyond the bounds of habitability. But it will create conditions unlike anything seen in the 300,000 years our species has existed — conditions that could wreak havoc through ecosystems and communities.

“As long as one or two organisms survive, there will always be life. I’m not concerned about that,” Judd said. “My concern is what human life looks like. What it means to survive.”