The boreal forests here in the Sami homeland take so long to grow that even small, stunted trees are often hundreds of years old. It is part of the Taiga – meaning “land of the little sticks” in Russian – that stretches around the far northern hemisphere through Siberia, Scandinavia, Alaska and Canada.

It is these forests that helped underpin the credibility of the most ambitious carbon-neutrality target in the developed world: Finland’s commitment to be carbon neutral by 2035.

The law, which came into force two years ago, means the country is aiming to reach the target 15 years earlier than many of its EU counterparts.

In a country of 5.6 million people with nearly 70% covered by forests and peatlands, many assumed the plan would not be a problem.

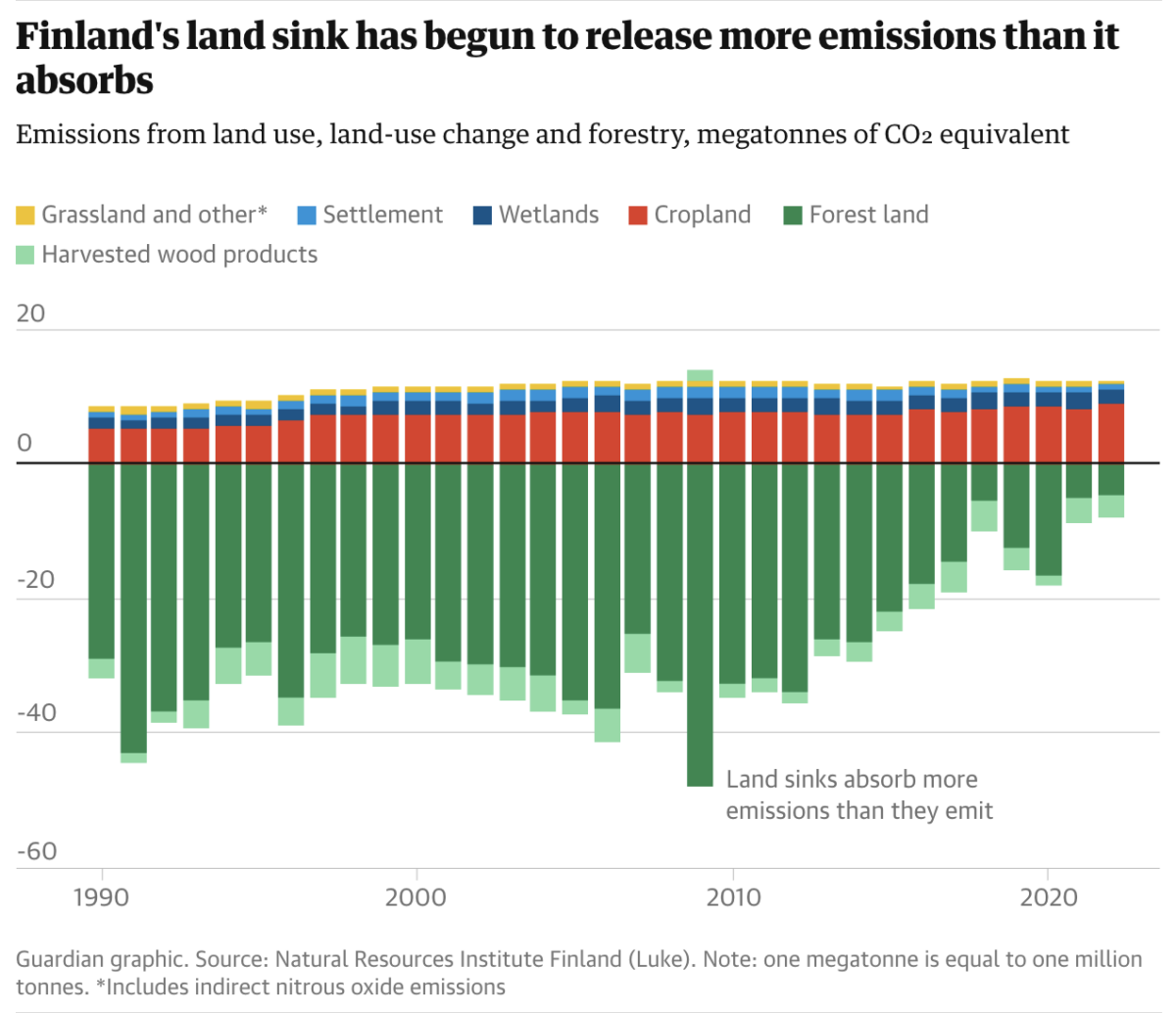

For decades, the country’s forests and peatlands had reliably removed more carbon from the atmosphere than they released. But from about 2010, the amount the land absorbed started to decline, slowly at first, then rapidly. By 2018, Finland’s land sink – the phrase scientists use to describe something that absorbs more carbon than it releases – had vanished.

Its forest sink has declined about 90% from 2009 to 2022, with the rest of the decline fuelled by increased emissions from soil and peat. In 2021-22, Finland’s land sector was a net contributor to global heating.

The impact on Finland’s overall climate progress is dramatic: despite cutting emissions by 43% across all other sectors, its net emissions are at about the same level as the early 1990s. It is as if nothing has happened for 30 years.

The collapse has enormous implications, not only for Finland but internationally. At least 118 countries are relying on natural carbon sinks to meet climate targets. Now, through a combination of human destruction and the climate crisis itself, some are teetering and beginning to see declines in the amount of carbon that they take in.

“We cannot achieve carbon neutrality if the land sector is a source of emissions. They have to be sinks because all emissions can’t be decreased to zero in other sectors,” says Juha Mikola, a researcher for the Natural Resources Institute Finland (Luke), which is responsible for producing the official government figures.

The reasons behind these changes are complicated and not fully understood, say researchers. Burning peatland for energy – more polluting than coal – remains common. Commercial logging of forests – including rare primeval ecosystems formed since the last ice age – has increased from an already relentless pace, making up the majority of emissions from Finland’s land sector. But there are also indications that the climate crisis has become a driver of the decline.

Rising temperatures in the most rapidly warming part of the planet are heating up Finland’s soils, increasing the rate at which peatlands break down and release greenhouse gases into the air. Palsas – enormous mounds of frozen peat – are rapidly disappearing in Lapland.

The number of dying trees also increased in recent years as forests are stressed by drought and high temperatures. In south-east Finland, the number of dying trees has risen rapidly, increasing 788% in just six years between 2017 and 2023, and the amount of standing deadwood – decaying trees – is up by about 900%.

The country’s forests, mostly planted after the end of the second world war, are also maturing, approaching the maximum amount of carbon that they can naturally store.

Bernt Nordman, from WWF Finland, says: “Five years ago, the general narrative was that the forests in Finland are a huge carbon sink – that actually they can offset emissions in Finland. This has changed very, very dramatically.”

These changes – while anticipated by climate scientists – are worrying policymakers. Finland is not alone in its experience of decline or vanishing land sinks. France, Germany, the Czech Republic, Sweden and Estonia are among those that have seen significant declines in their land sinks.

Drought, climate-related outbreaks of bark beetle, wildfire and tree mortality from extreme heat are ravaging Europe’s woodlands on top of pressure from forestry. Across the EU, the amount of carbon absorbed by its land each year fell by about a third between 2010 and 2022, according to the latest research, endangering the continent’s climate target.